Sustainability in Singapore’s Sport Industry

Ray Lim takes a look into the conversation surrounding the sustainability of Singapore’s Health and Wellness Industry, as well as their professionals.

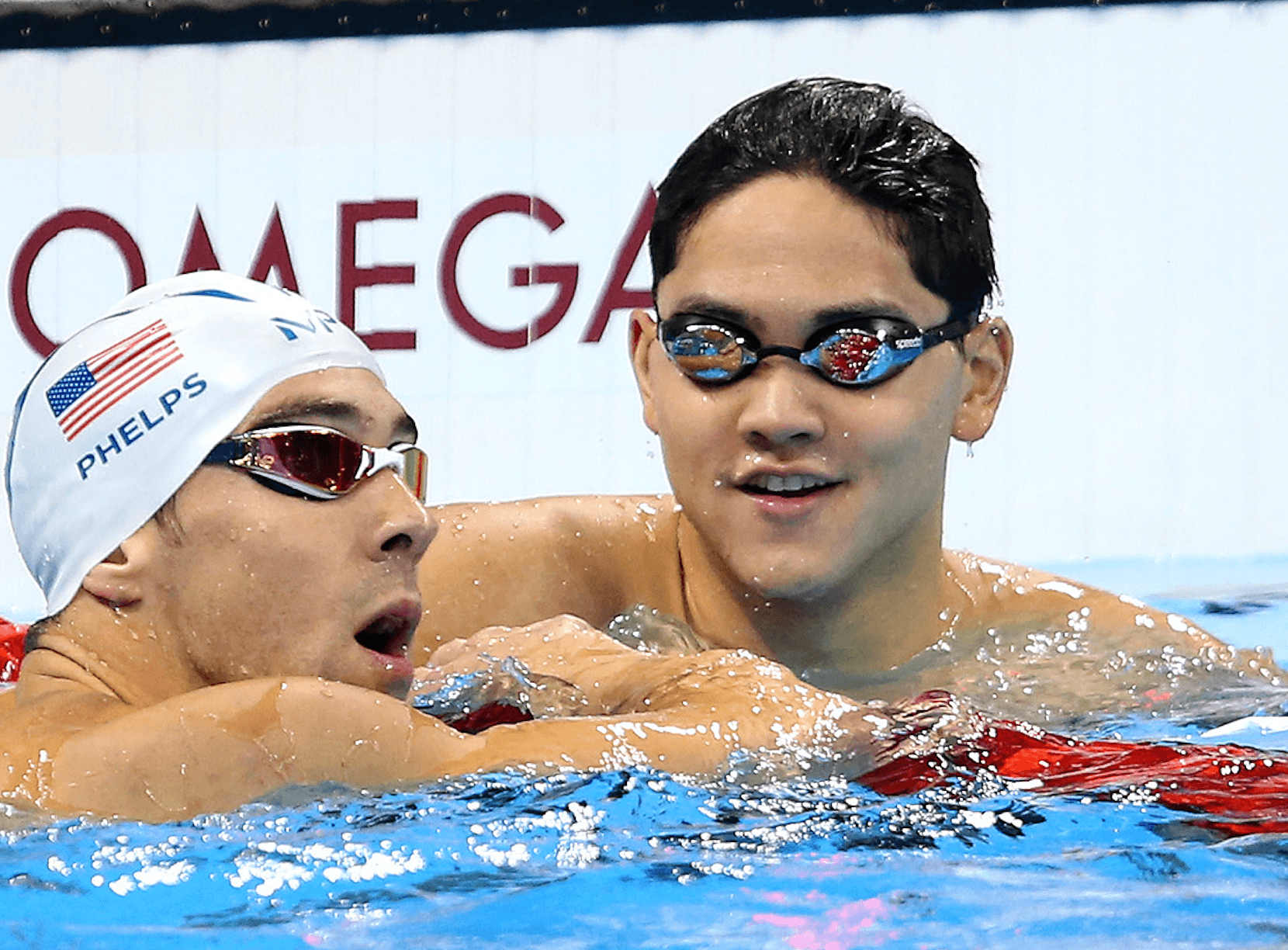

Michael Phelps and Joseph Schooling (from left) at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Photo taken from shutterstock.

BY

Ray Lim

Places Section Editor

Hype Issue #53

Published on

June 29, 2021

When you think of the sport industry in Singapore, it is likely that a Physical Education (PE) teacher or Olympic athlete comes to mind.

Singapore has always had a strong position in nurturing a healthy lifestyle amongst the populace. After gaining independence in 1965, the government called on the nation to cultivate an inclusive and robust sporting community through sports participation; it was seen as a way for our multiracial society to bond.

The Singapore government introduced the National Fitness Exercise (NFX) in 1969 to encourage physical fitness among the masses, leading to the establishment of the National Sports Promotion Board (NSPB) in 1971. With the main goal to promote, assist and organise international competitions, the NSPB worked with national sports associations and the Singapore National Olympic Council to manage and maintain sports facilities and stadia.

Michael Phelps and Joseph Schooling (from left) at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Photo taken from shutterstock.

Singapore is the most generous country in terms of its financial awards for their Olympic winners. They awarded Joseph Schooling a total of US$1,040,000 (S$1,398,00) for winning the gold medal. This trend of giving big payouts to national athletes works to incentivise younger athletes to train and aspire to be the best.

The opening of Singapore Sports School in April 2004, by the then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, marked Singapore’s start to this race to be the best, by providing athletically talented young individuals with an opportunity to pursue their sporting dreams and potential.

“Sport is a celebration of the human spirit. Some of us do it just for fun or to keep fit. Others use it to gain honour and glory,” said then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, in a 2001 interview at the Committee of Sporting Singapore. “Whatever the reason, sport invigorates the body and mind. It also deepens the sense of community and fosters enduring friendships.”

The sport industry in Singapore has evolved from just being a form of recreation to accommodate the masses, to a multi-million dollar industry, with its roots in advertising and sponsorships. There are a multitude of platforms that accessorise the sport industry to promote their brands such as Nike, Puma and Adidas.

In an article by SportPro, Nestle Milo was said to have invested some US$2.2 million (S$2,900,000) in youth sports in 2010.

“Singapore’s young people under the age of 25 account for about one-third of our population. This 1.16 million-strong demographic will be our next generation of elite athletes, coaches, officials, volunteers, administrators and visionaries,” said Oon Jin Teik, chief executive of Singapore Sports Council (SSC). “They will ensure the expansion and self-sustainability of our sports sector. Hence, we need to prepare them to take on these roles for Singapore.”

Oliver warming up for a local race. Photo courtesy of Oliver Chong.

Oliver Chong, 18, a professional cyclist, has been part of the national cycling squad for over a year and secured third place in a local criterium by the Singapore Cycling Federation (SCF). He was well on his way to nationals before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, stopping him in his tracks.

“Entering the field of professional cycling is extremely difficult for a Singaporean like myself. A road bike can cost up to $20,000,” said Oliver. “I feel that professional cycling is only viable if you are willing to be motivated and committed, at the expense of sacrificing your time with friends and family.”

Take the pinnacle of cycling competitions, the Tour de France, for example. It is a grand tour for cyclists consisting of 21 stages, with usually 200km–300km per stage. These professional cyclists have to go through a stage almost every day for 21 days to win the grand prize of €500,000 (S$800,596). However, the training alone for these competitions is extremely time-consuming, even in the local and professional continental races.

Oliver recalls being put on a training plan for four months which required him to ride for at least two hours a day on the weekdays, and up to six hours a day on the weekends. That adds up to about 600km a week, which he found to be “truly mentally draining”.

“It would be an amazing career if you do it well. You get to ride the best, most technologically advanced bikes, ride in the most gorgeous alps the world has to offer and basically get paid to do what you love and travel the world while doing it,” said Oliver.

As glorious as it sounds, Oliver mentioned that it would not be feasible in the long term, at least for Singaporeans, as the level of commitment would be hard to keep up with. This can be attributed to factors such as the compulsory two years of National Service (NS) in which all Singaporean and Permanent Resident (PR) men are required to serve, as well as the demanding schedule of the Singaporean education system. As such, one simply would not have the time or stamina to follow through with such a career.

In Singapore, there are three educational institutions for students pursuing the arts: Laselle College of the Arts, School of the Arts, and Nanyang Academy of the Fine Arts. Over 6,100 students are enrolled in tertiary art courses or in the School of the Arts.

Management and Coaching

The National Stadium at Kallang. Photo courtesy of Isaiah Chua.

Singapore’s sport industry is not just centered around athletes. Many sports hubs, such as the National Stadium and Our Tampines Hub, are built with the main goal of advocating an active lifestyle among Singaporeans of all ages. As grand and awe-inspiring these multi-million dollar sports hubs are, how useful would they be to the residents, if not for the people who manage them?

Mr Chong Kai Sheng, 27, told HYPE about how he first stepped foot into the sport and fitness industry when he was only 22 years old. He began by giving private personal training as a part-time job while studying in university, charging $40 to $70 per session.

Our Tampines Hub, a sports and recreation center. Photo courtesy of Ray Lim.

“I [now] manage a sports and recreation facility (Our Tampines Hub),” said Mr Chong. “I’m required to attend to a wide scope of responsibilities on a day-to-day basis, that entails and is not limited to the following areas: facility management, programme and event outreach, staff management, partners and stakeholder management, general operations and more.”

It is inspiring how his career in the sport industry has blossomed from giving private training as a part-time job to managing a multi-million dollar facility such as Our Tampines Hub.

Jakeem Juraimi, 19, is one of his employees at Our Tampines Hub.

“As an active champion, we help with the backend of running the facility to ensure smooth operations day-to-day,” said Jakeem. “We are involved in planning events such as camps, helping to facilitate and direct the participants, as well as planning fitness events such as zumba, yoga and spin classes for the participants.”

Activities such as Zumba and spin classes see that Jakeem earns a 70 per cent cut of the class, in which each student pays anywhere from $50 to $120 per lesson. There are over 30 students in each class, but classes have dropped to a limit of 14 students due to the current pandemic measures.

“I did my degree in Business Administration, and specialised in Financial Analysis. While it may seem unrelated [to] my current work, there is a certain translatable knowledge and skill set when it comes to management. Primarily, business acumen and concepts of organisational behavior are applied at the workplace daily,” said Mr Chong.

This is a testament to how one’s career path is not solely determined based on their academic area of study, as exemplified by Mr Chong’s career in Our Tampines Hub. Although sports and wellness may not be perceived as an ideal industry by many Singaporeans, it encompasses versatile job scopes that incorporate the use of diverse skill sets and backgrounds.

“I studied sports management in Institute of Technical Education (ITE), and went in with the passion for the sport industry. What I studied influenced my career path as it only allowed me to further expand my knowledge in this industry. It has given me more opportunities to earn money and make a career out of what I enjoy,” said Mr Juraimi.

He plans to further his studies and improve his opportunities to advance his career in sports and fitness, as well as to have a larger impact on the industry. His study in the course and passion for the sport industry emphasises how different courses of studies can still lead to a fulfilling career in the sport industry.

“I do believe that [the] sports and fitness industry is sustainable and there [is] still much room for growth. It is a viable option to be working in this industry. Much like F&B (Food & Beverages), it will not go out of business,” said Mr Chong. “In the context of a modern fast-paced and often high-stress environment of today, I do see sports and exercise as a legitimate need.”

With the recent trend of a mindset shift towards prioritising personal wellness, the industry has to remain sustainable and lucrative for those who are passionate, innovative and constantly challenging themselves to improve on their personal wellbeing.

The need to exercise is on the rise with many individuals engaging in regular exercise regimens to better their health amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, as stated in an article by The Straits Times that pointed out how the pandemic was a weighty burden for some, yet a push to exercise for others.

“With this pandemic, even though we may not be able to do classes physically, virtual workouts are the trend which pays a lot and at the same time, necessary for people to keep fit,” says Jakeem.

Even as Singapore progresses into the age of modern technology, there is not much cause for concern of the automation or implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) replacing the human interaction required within the sport industry.

“There will always be a future, it is just how one approaches the situation which will determine the overall viability of their career,” Jakeem said.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the viability of the sport industry in the long term for the athletes of Singapore is unknown. With younger and stronger competitors taking over year after year, the industry is ever-changing.

The sustainability aspect then falls on the coaches and private trainers, who work to help these future generations improve themselves or to aid the general populace in leading a healthier lifestyle. It is in this critical aspect of the industry, that draws on past experiences to teach the new generation, that would make the sport industry in Singapore a sustainable one.

relax

smooth jazz

sleep jazz

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 19654 more Info on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 57540 additional Info to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 98904 more Info to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

Start your study for free at NTU! Explore our diverse programs in engineering, agriculture and administration, offered at the diploma, bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD levels. Visit the NTU homepage to learn more: https://ntu.edu.iq/undergraduate-programs/

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 47140 more Information to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: hypesingapore.com/index.php/2021/07/01/sustainability-in-singapores-sport-industry/ […]

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.